Wells Fargo firing of employees over 'keystroke simulation' shows systemic failure, says expert

Wells Fargo caught headlines last week with the news it had fired about a dozen employees for “simulation of keyboard activity”, according to Bloomberg.

It’s the latest development in the ongoing battle over employee rights to privacy and work-life balance, versus the employer’s right to maintain productivity.

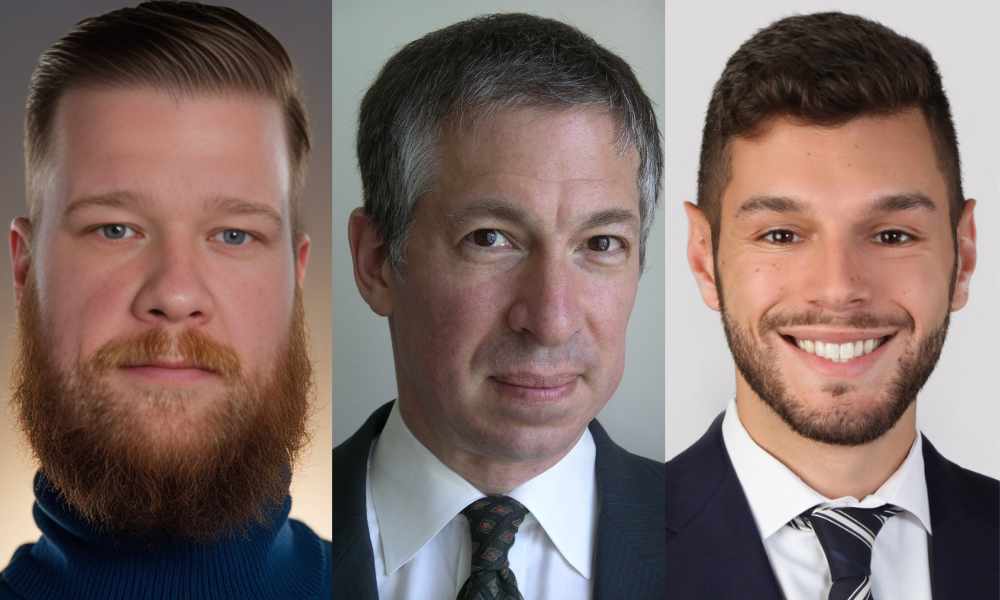

“Give people the right tasks, give them interesting work, interesting projects. Give them something which they have to deliver and be accountable for, and then you have no problem,” says Vaclav Vincalek, virtual CTO and founder of 555vCTO in Vancouver.

“It's not just ‘Find out who's cheating and fire them.’ That's not changing the problem.”

The question: Why are we monitoring employees?

If employees know that they are being monitored for nothing but keyboard or mouse activity, with consequences for not reaching a quota, then they will focus their energies accordingly, Vincalek says.

Such practices also indicate an unhealthy culture, he says.

“It's easy to assign blame on one party or another,” Vincalek says, suggesting it can mean the overall culture at a company involves “people who have nothing else to do than being monitored, or spend time monitoring others, without delivering real work.

“I would say that's the story here: Who has the time to fake work, and who has the time to monitor it?”

Rather than assessing whether employees are breaking arbitrary rules about hours spent at a screen or typing characters into a keyboard, HR and employers should rather be asking if employees are engaged in doing meaningful work.

“If I motivate you that you get paid by a number of characters, well, you'll be hitting ‘enter’ and ‘space’ so many times, so you get paid more,” says Vincalek.

“Do we have better [products] because of that? No, but you’re hitting your quota. That's when you employ a keystroke hitter.”

Focus on timelines, tasks rather than keystrokes, hours

The main mistake organizations are making, including Wells Fargo, is sending incorrect information to employees about what is valued from their work. When employers measure hours and keystrokes, it sends the message to employees that their boss cares more about monitoring their activity than what they are producing, he says.

Instead, employers should focus on agreed timelines for projects and tasks, and the quality of outcomes, Vincalek says. Resorting to monitoring things like keystrokes or screen activity indicates that employers don’t know the work their employees are doing, and don’t know how to measure it.

“The delusion that you can control people remotely with various monitoring tools, that's only when people get paid by the hour with no actual measurable output,” he says, or if employees have been given tasks that “are so nonsensical that they cannot measure the output of their work.”

Employees are also highly adaptable, which is why behaviours such as simulating work can become a cultural activity, says Vincalek.

“You are always parachuted into an environment, and you learn the rules of the game, and you start following the rules of the game,” he says. “You start working for a company which doesn't care that you come to the office; the only thing they ask you is to be eight hours in front of the computer. These are the rules … what people do. They are highly adaptable, they understand the rules and gaming the system, every single time.”

Work simulation technology not new

Wells Fargo missed a valuable opportunity to learn about what is clearly a systemic problem, Vincalek says, advising HR leaders to take a much different approach to such behaviours in their workplaces, before there is any evidence of it.

“Don't treat employees like children, and really take the time to understand what people actually do,” he says. “For HR people, it's very difficult, because they are not subject matter experts.”

Upon hearing of work simulation at their organization, HR leaders might have a gut reaction to go to IT and find out who is doing it, Vincalek says. But he urges employers to take a different tack.

“The homework is to find out what is the best method, which is the most useful and friendly method to find out if people are happy and they work on interesting tasks, and if the work makes them satisfied,” he says.

“These are actually very deep organizational questions, and just trying to go and check people, what they do, is definitely the wrong way of doing it.”