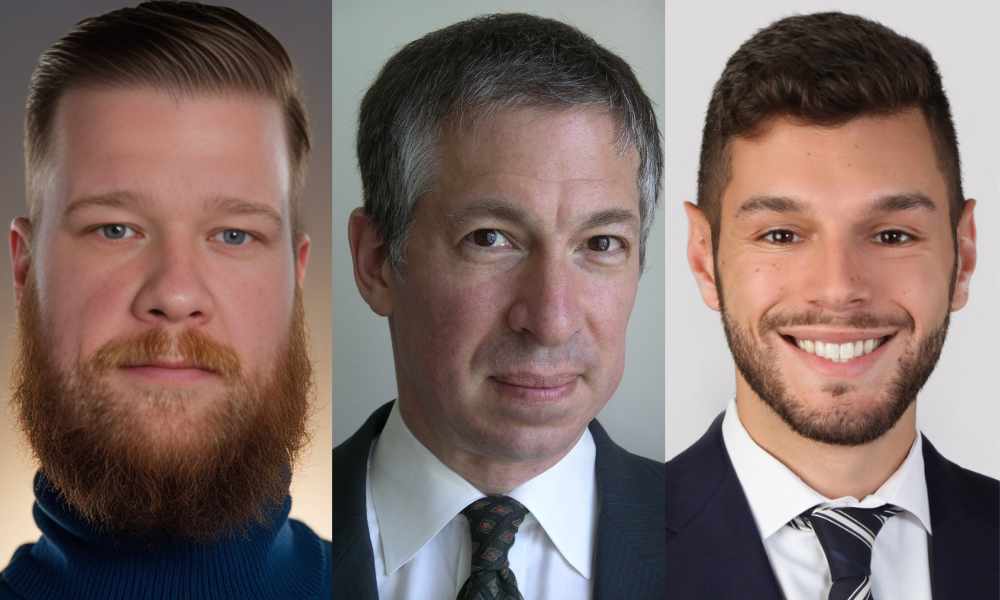

'They were effectively weeding people out without knowing it': ICC CEO explains underemployment of high-skill immigrants – even during labour shortages

The issue of immigrant underemployment remains a persistent problem in Canada, despite policies aimed at integrating highly skilled global talent into the workforce.

But why?

“For the longest time, research has focused on racism and discrimination as the key drivers, and these certainly exist,” says Daniel Bernhard, CEO of the Institute for Canadian Citizenship (ICC).

While that explains why a company would hire John instead of Ahmed, for example, even with labour shortages in 2022 and 2023, highly skilled immigrants were still being overlooked.

“John wasn't around, and Ahmed still wasn't getting hired. And so we were wondering how it was possible for a high-skilled labour shortage to coexist with underemployment of an extremely highly skilled group.

“And that caused us to probe a little bit deeper and realize that these companies were actually leaving millions of dollars on the table by keeping this talent parked on the bench.”

Culture of non-ambition in Canadian organizations leading to lost revenue

A new report by the ICC and Deloitte shines light on the challenges employers are facing when hiring newcomers to Canada, in talking to over 40 business leaders from a range of sectors such as mining, energy, technology, not-for-profit, finance and education.

According to the Talent to Win report, the Canadian economy lost $54 billion in GDP potential in 2022 due to labour shortages. Even though Canada will grant permanent residency to 1.5 million people over the next three years, many immigrants already in the country remain underemployed, the report states.

Further, 30 per cent of new Canadians under 35 are planning to leave the country within the next two years, mostly due to underemployment.

One major roadblock to hiring immigrant talent is what Bernhard describes as a “culture of non-ambition” within Canadian workplaces.

Many corporate leaders reported that even when data showed that teams including immigrants outperformed others, there was resistance to change within their own organizations, including apathy towards innovation and feelings of being threatened by newcomers. This closed mindset holds Canadian businesses back from realizing the full potential of global talent, Bernhard says.

“Hiring managers felt threatened by people who worked harder than they did, and who came from countries with more of a hustle culture, and they were able to shut these people down by saying that they needed to have better respect for work-life balance,” Bernhard says.

“There's evidence in place that this experience is being shunned for cultural reasons within Canada's economy. Despite evidence that the firms who make use of this talent get ahead, there were many people within these firms that were actually less interested in getting ahead than just maintaining their status quo of how they do things.”

Blind spots in DEI hiring frameworks

Another issue limiting the hiring of immigrant talent is the gaps in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) frameworks, Bernhard says.

Many companies prioritize gender and racial diversity but overlook the significance of global experience; this results in visually diverse workforces, but that diversity might not include the valuable international perspectives that immigrants can bring.

“Many firms that seek to boost the representation of their workforce don’t actually consider the country you were born in as a factor, and so you could have a very visually diverse workforce, but those people could have all been born in Canada and all gone to Canadian universities, and so you don't actually bring in global experience like you think you do.

“Once [employers] started tracking, they got to see that actually they were effectively weeding people out without even knowing it.”

This failure to incorporate global perspectives can prevent companies from staying competitive, especially in industries that benefit from innovative approaches developed abroad. For example, immigrants from countries like India and China, which have advanced quickly in digital industries, often bring valuable expertise that Canadian companies could leverage to improve productivity.

“Some of these countries where immigrants are coming from have made incredible advances over the last 20 or 30 years, and in many cases, now surpass Canada, especially when it comes to the digital economy,” he says.

“We need to open our minds to the possibility that we have things to learn, that this is not just about validating whether an immigrant is ‘good enough for us’, but actually saying, ‘Hmm, this person's coming from another place. What can they teach us?’ I think reframing that talent in our minds can then open us up to the opportunity and all the value that it delivers in the workforce.”

Overcoming regulatory hurdles with creative ‘workarounds’

The survey found that Canada’s immigration system is a significant barrier to hiring immigrants, with the administrative and regulatory burden of hiring internationally, or even onboarding immigrants already in Canada, proving too daunting of a task, especially for SMEs.

However, as Bernhard notes, some companies have found creative solutions to these challenges, “workarounds” that enable employers to reap productivity gains as well as other unexpected benefits.

One natural resources company, for instance, dropped a requirement for heavy equipment operators to have winter driving experience, which had previously disqualified many immigrants: “What they actually found was that people with no experience driving with snow were more careful and therefore had fewer accidents,” he says.

Similarly, a construction company bypassed safety concerns related to language barriers by creating unilingual teams of Ukrainian and Hindi speakers, increasing safety and reducing lead times.

“These leaders really understood, even the frustrated ones really understood, that being able to make use of talent from around the world with different global experiences is such a competitive edge, it brings the ability to do things that your competitors don't know how to do. So, they were really motivated.”

Business imperative for hiring global talent

Bernhard points out that addressing immigrant underemployment is not just about inclusion — it’s a business imperative; he urges employers to stop viewing immigrant hiring as a moral obligation and instead see it as a way to gain an edge in the market: “Don’t do this for moral reasons. Don’t do this to be nice. Do this to win.”

The Talent to Win report offers several strategic opportunities for employers looking to better use immigrant talent. One key recommendation is for companies to collect data on country of origin and year of arrival in their DEI frameworks. This data can help track immigrant outcomes and ensure that companies are not unintentionally excluding global talent.

Another strategy is to spread success stories within organizations to demonstrate the benefits of hiring immigrants. When leaders share the positive results of diverse, globally experienced teams, it can inspire others to follow suit. Plus, some employers create specialized immigrant hiring teams to support immigrant employees in their integration and growth, including more structured hiring and onboarding practices.

“Immigrants in particular do much, much better when there's structured training and onboarding happening within the company,” Bernhard says.

“We know that training of the workforce in general is declining across the Canadian economy, that many employers expect people to just show up with skills … because sometimes these things are just left assumed or implicit, and immigrants lack that implicit knowledge, and they're held against them later, and it prevents the firm from being able to make use of their talents.”

By investing in structured training, onboarding programs, and global hiring frameworks, Canadian employers can not only reduce labour shortages but also drive better business outcomes. Bernhard stresses that due to the current economic landscape, the time to act is now.

“Canada, from a growth and productivity perspective, we’re down two goals late in the third, and we’ve got some of our best talent parked on the bench. And that just doesn’t make any sense.”