'We're just trying to cram people into these pre-established programs': academic says employers need to provide more personalized mental health support

A new survey of Canadian workers has revealed alarming statistics: 23% had thoughts of self-harm or suicide in the previous two weeks, and 36% had such thoughts in the previous year.

"These statistics serve as a wake-up call for employers to recognize and address the mental health crisis within the workplace," said Ramakant Vempati, president and co-founder of mental health provider Wysa, which surveyed 2,000 workers across all industries in Canada in February.

"Even one person contemplating suicide or self-harm is too high. The average person will spend one-third of their lifetime at work, so companies have an opportunity to play a pivotal role in supporting individuals."

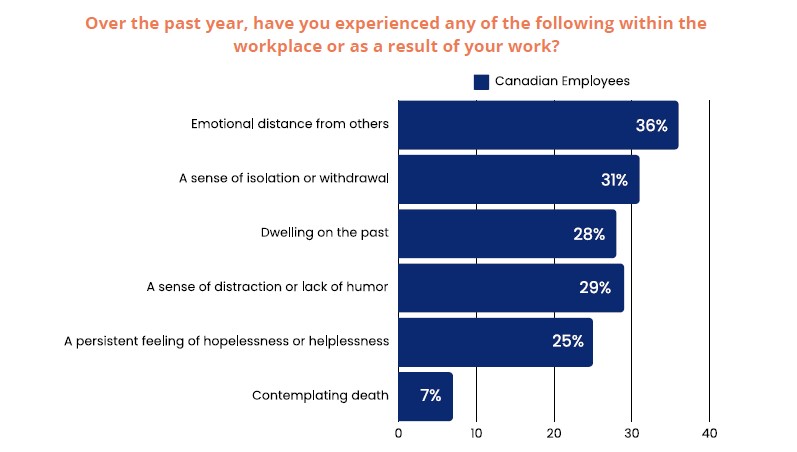

Other low feelings cited by the survey include:

- isolation or withdrawal while at work (31%)

- emotional distance from others (36%)

- dwelling on the past (28%)

- a persistent feeling of hopelessness (23%)

Mental health crisis prevention not part of conversation in workplaces

The report shared that one in five Canadian respondents worry about a colleague’s potential for self-harm or suicide, but 68% of workers have not received training on how to handle a co-worker’s severe depression.

This lack of training is one of the reasons these statistics are so high, says Jason Walker, associate professor and program director of industrial and organizational psychology at Adler University.

“We do not train people in the workplace to identify when someone's struggling based on mental health,” Walker says. “What we look for is, what is their work performance? Their work performance is down, they're not meeting their goals, they're being really moody. And there's no mechanism outside of human resources – which is the organization's police department, in a lot of cases – to deal with it.”

Rather than focusing on prevention of mental health issues due to stress, he continues, current workplace policies focus more on addressing crises after they’ve happened. They should instead be figuring out how to keep those crises from happening in the first place.

“As much as COVID helped us when it came to talking about mental health, stigma in the workplace around mental health is as strong as it's ever been.”

Source: Wysa “Colleagues in Crisis Report”

Workplace policies don’t do enough to prevent suicide and self harm in Canadian employees

Although there is legislation in Canada preventing employers from discriminating against employees for mental health status or disability, says Walker, there is still stigma around mental health challenges that many employees find impossible to surmount.

“We know that employers have obligations and accommodations and labour laws to protect employees around their mental health,” he says. “However, one of the interesting things we don't talk about when it comes to diversity and inclusivity is people in the workplace with mental health.”

Even if an employee has permission from a doctor to go on a mental health leave, there may still be hesitation on their part due to how that leave will be perceived by the organization, Walker says. This differs from physical or other illnesses that aren’t stigmatized.

“You're stigmatized for taking sick leave,” he says. “It's not looked at as ‘Okay, this person's looking after themselves’ or ‘We as an organization are going to support this person to be healthy.’ It's more, ‘Either the work's going to wait for you, or you're not strong enough to get through it.’”

Employee wellness apps don’t prevent suicide or self harm

There are about 4,500 deaths by suicide each year in Canada, according to Statistics Canada – that’s about 12 per day. Recent research has shown that about one in five Canadians have a diagnosable mental disorder and about one in seven have an addiction, Walker says.

“What that says to me is even if you're working in a team of five people, five or seven people, at least one person is going to have some sort of mental health disorder or an issue that requires help,” he says.

Wellness programs that mostly entail an app and a limited number of therapy sessions for specific ailments don’t cut it against self-harm and suicide, Walker says, because they place the burden of getting help onto the employee.

“Until organizations actually take ownership of the fact that they need to protect employees, they have a duty to protect employees in a range of aspects of life, we're really just trying to tread water,” he says.

“Even if you look at the bottom line, what we're doing isn't working, because that just leads people to burnout, and then they're off for three weeks or five weeks or six months, dealing with really severe mental health issues typically related to the workplace.”

Source: Wysa “Colleagues in Crisis Report”

Make workplace mental health support employee-led

Instead of health and wellness benefits that provide minimal support for suicide prevention, Walker says, employers can offer a “basket of service” instead – allowing employees to choose what benefits would best provide the help they need.

But that requires talking to them, he says.

“The number one step is actually taking a step back and asking employees what they need and what they want,” he says, saying that many organizations offer rigid mental health programs and expect employees to fit into them.

“I think we really need to turn that upside down … as opposed to HR sitting in a room with the benefits insurance company that's looking to save money at the end of the day, but where are the employees? Where are their ideas? Because people will engage in it if it's their idea, and it doesn't have to be astronomically expensive.”

Employees want more mental health support from employers

Only 43% of the Wysa respondents said their employer takes proactive steps to address workplace mental health. Thirty-six percent of respondents said their employer sees mental health as a personal or outside-of-work matter.

The report also revealed that over half (56%) of respondents between the ages of 18 – 24 have been bothered with thoughts that they would be better off dead or of hurting themselves in the last year. Add to this the stress created by workplace harassment and bullying, which also causes suicidal thoughts, and the responsibility for mental health care should lie squarely with employers, Walker says.

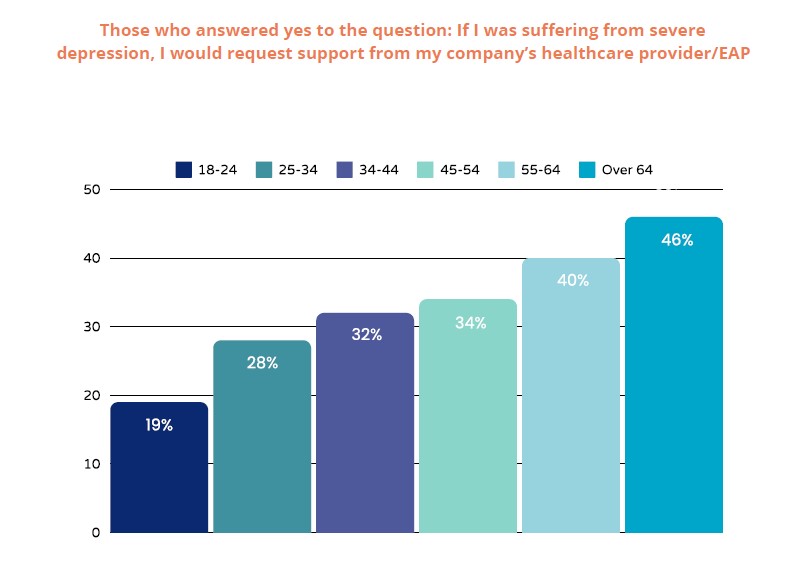

And he says Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) are the “bare minimum responsibility” of employers.

“The problem is that we're just trying to cram people into these pre-established programs,” Walker says.

“I think it's incumbent upon organizations who are innovative and have leadership that is interested in their employee wellbeing, not just to say, ‘Here's the program we designed for you, go to the app.’ It's more ‘What will work for you as an individual and as a team?’”

Additionally, employers should be recognizing their employees, not just annually but throughout the year, monthly or quarterly, he adds. Giving employees the day off for their birthday, for example, may seem like a small token, but can make a huge difference to an employee who is struggling with their mental health and approaching burnout,.

“People want to feel heard and they want to feel respected. The employer has a lot of power, the employee doesn't,” Walker says. “Things like that, it seems small, but when you're in the grind and all you need is a break, or all you need is an appointment with a therapist where you can actually have a long-term relationship versus three sessions, that is the basic minimum.”