U.S. appeals case to determine whether federal safety law should apply to SeaWorld

(Reuters) — A killer whale, the lawyer-son of a Supreme Court justice and the grisly death of wildlife trainer will play roles in a November U.S. appeals court case that could forever change marine park operator SeaWorld's marquee entertainment.

The signature attraction for the company's three U.S. theme parks has been shows featuring the black-and-white killer whales or orcas, including several named Shamu, performing flips and other stunts under the direction of trainers who historically have been in close contact with them.

But that changed after the February 2010 death of Dawn Brancheau, a 40-year-old trainer. She drowned after being pulled into a pool by Tilikum, a 12,000-pound bull orca, at SeaWorld's site in Orlando, Fla.

In August 2010, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) fined SeaWorld $75,000 for three safety violations, saying it had exposed its trainers to a hazardous environment and violated a part of the Occupational Safety and Health Act known as the general duty clause.

OSHA, a part of the U.S. Labor Department, demanded SeaWorld make certain changes, notably, physically separating the killer whale trainers from the orcas during show performances.

SeaWorld is appealing the broad application of a federal safety law meant to protect workers in unusual circumstances. The case will come before a three-judge panel of the U.S Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit on Nov. 12.

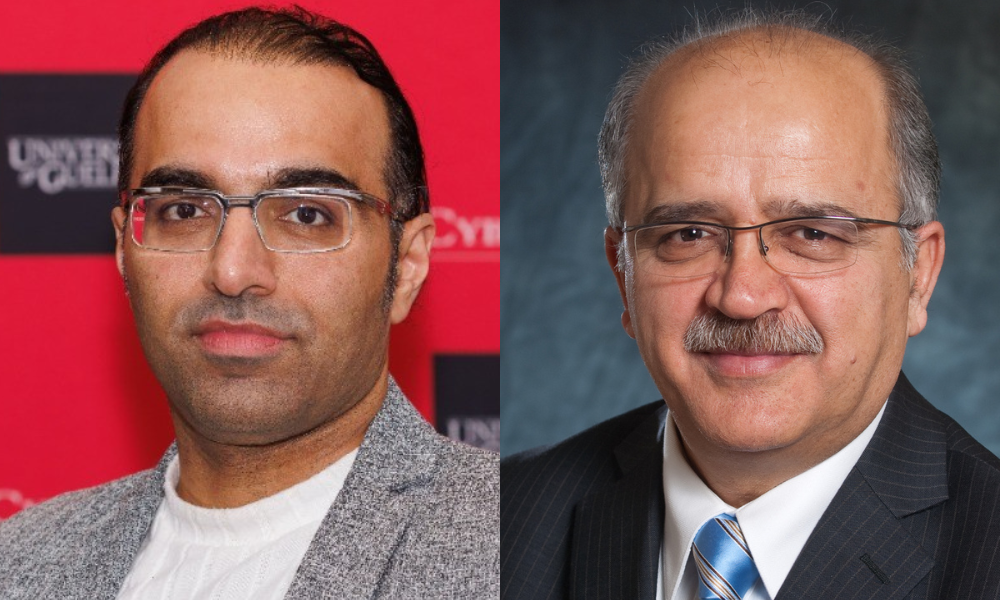

With animal rights activists watching, Eugene Scalia, son of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, will represent SeaWorld in its fight against a federal order that sharply criticized the marine park operator's safety measures.

Ken Welsch, an administrative law judge of the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission, in 2012 upheld the OSHA citations but downgraded one of them to "serious" from "willful," effectively reducing the fine to $12,000 from $75,000.

In appealing Welsch's decision, SeaWorld argued OSHA's fine was premised on an overly broad view and "novel application" of the general duty clause, which mandates that employers keep their workplaces free from "recognized" hazards. In a 60-page opening appellate brief, SeaWorld called the case "fundamentally misguided."

"The clause cannot be used to force a company to change the very product that it offers the public, and the business it is in," SeaWorld wrote. "The clause is no more an instrument for supervising the interactions between whales and humans at SeaWorld, than it is a charter to prohibit blocking and tackling in the NFL or to post speed limits on the NASCAR circuit."

Blackstone floated SeaWorld

SeaWorld Orlando is owned by SeaWorld Entertainment , which was taken public in April by private equity firm Blackstone Group LP.

SeaWorld has brought in a high-powered team from law firm Gibson Dunn and Crutcher to press its appeal. The team includes Scalia, formerly the U.S. Labor Department's top lawyer. He is joined by Baruch Fellner, also a former U.S. Labor Department lawyer, who founded Gibson Dunn's OSHA practice.

The general duty clause is OSHA's "catch-all" clause that it wields against companies in situations where there is not necessarily a dominant, clearly articulated safety standard, said Melissa Bailey, an attorney at Ogletree, Deakins, Nash, Smoak and Stewart who represents employers in OSHA cases.

The cases can be difficult to pursue because OSHA must show what is a "recognized" hazard when there are not clear industry standards, she said.

"In cases like the SeaWorld case, that's a unique animal — no pun intended," said Bailey.

Orcas and people

The penalties OSHA can bring are relatively small, but a key issue is at stake for SeaWorld — whether its performances can include killer whales and humans in close contact.

"OSHA penalties are not that great," said Bailey, comparing them to fines that other agencies can levy. "But it's rarely the fine that drives the litigation. It's often the abatement cost, and having this on your record."

SeaWorld trainers have not been in the water with an orca since the drowning, said SeaWorld spokesman Fred Jacobs.

SeaWorld's primary concern in the litigation is the long-term effect that OSHA's requirement of separation of humans and killer whales could have on the shows. In court papers SeaWorld called their interaction "integral to its mission."

"We want to continue to display these animals in a way that assures their health and well-being and is safe for our zoological staff," Jacobs said in an email. He declined to comment further, citing the pending litigation.

Human-orca interaction has long been filled with controversy, revisited earlier this year with the release of the movie "Blackfish" about Brancheau's death and Tilikum's 30-year career as an entertainer and stud for other captive whales. SeaWorld has criticized the film as "inaccurate and misleading."

The U.S. Labor Department says SeaWorld knew close human-orca contact was dangerous — Tilikum has been involved in other human deaths — and it routinely took steps to minimize hazards.

"The Secretary (of Labor) did not overreach in applying the general duty clause to SeaWorld in this case because the clause is meant to address unusual hazards for which there are no promulgated standards, just like the hazard present here," the U.S. Labor Department wrote in a brief.

Two animal-rights groups — People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals and the Animal Legal Defense Fund — have weighed in with an amicus brief to support the U.S. Labor Department. The groups, strong critics of SeaWorld in the past, wrote in the brief that prolonged captivity has forced the orcas to behave aggressively.