Ontario court upholds clause in Uber contract that gives jurisdiction of disputes to arbitration in the Netherlands, where Uber is headquartered

In the recent case of Heller v. Uber Technologies Inc., the Ontario Superior Court of Justice dealt with a case in which David Heller, an Uber food delivery driver, attempted to bring a class action on behalf of all Uber drivers against Uber. Heller sought a declaration from the court that all of the drivers are employees of Uber and thereby entitled to the benefits of Ontario’s Employment Standards Act, 2000. Uber brought a motion to the court to stop the action on the basis that any complaint by Heller would have to be dealt with by way of arbitration in the Netherlands.

As the court noted, Uber carries on a global business in which it characterizes itself as a vendor of “lead generation services” which it sells to transportation providers. It denies that it is a transportation company. There is a fierce debate, yet to be resolved, about whether Uber drivers are independent contractors or employees.

The main Uber company is incorporated under the laws of the Netherlands and has its offices in Amsterdam. Uber Canada Inc. is a Canadian company that simply provides marketing and administrative support for Uber apps in Canada. It has no contractual relationship with the users of the Uber apps.

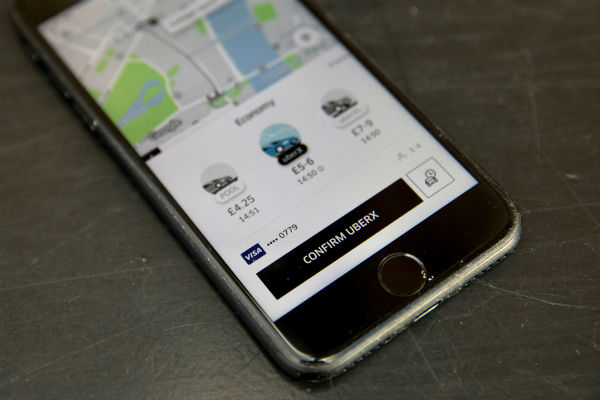

Uber’s business model is to licence a “Rider App” to consumers, and a “Driver App” to drivers who use it to open an account and become a driver. Drivers respond to ride requests and are paid through the Driver App. In exchange for providing the Driver App, Uber charges the driver a fee.

A similar business model is used for consumers who wish to order food from restaurants and have it delivered to them.

Drivers enter into service agreements electronically under which they are granted a licence to use the Driver App. The service agreements specify that the parties are not in an employment relationship.

Each service agreement is stated as being governed by the law of the Netherlands. It contains an arbitration clause that requires that any disputes arising in any way connected to the agreement must be resolved by arbitration in Amsterdam.

Heller entered into a service agreement in 2016. Several months later, he started his proposed class action seeking a declaration as to his employment status and a finding that Uber had violated the Ontario Employment Standards Act. He did so in the face of the arbitration clause requiring all disputes to be determined by arbitration in the Netherlands.

The Supreme Court of Canada has made it clear that the court will enforce mandatory arbitration clauses unless it is clear that the dispute falls outside the scope of the clause. Where it is unclear as to whether or not the dispute falls under that clause, the arbitrator will have the power to rule on that issue and determine the limits of his or her own jurisdiction. Accordingly, the court will defer the issue of jurisdiction to the arbitrator. In this case, the court was satisfied that it should be left to the arbitrator to decide whether he or she has jurisdiction to determine whether or not Uber drivers are employees.

The court pointed out that there is a “very strong legislative direction” under the arbitration statutes and numerous cases holding that the court should only refuse to refer a matter to arbitration if it is clear that the dispute falls outside of the arbitration clause. This was not such a case.

As a practical matter, of course, this decision will almost certainly end the matter. The idea that any Canadian driver would actually commence an arbitration proceeding in the Netherlands over this issue is difficult to take seriously given the practicalities involved.

The point to be taken from the case, is that before agreeing to the terms of a business relationship where the contract contains an arbitration clause, some attention should be paid to it. In situations like Uber, where all of the documentation appears online and there is no actual negotiation of any of its points, it is all too easy to simply click “I Agree” without reading the provisions to which one is agreeing. When a contract requires disputes to be arbitrated in some foreign country, the person signing it needs to know that enforcing his/her rights will be very difficult and expensive. That is something that people should recognize at the outset of a business relationship, and not simply once a dispute arises.

For more information see:

- Heller v. Uber Technologies Inc., 2018 CarswellOnt 1090 (Ont. S.C.J.).

A. Irvin Schein is a senior partner and chair of the Litigation Group and Class Action Group with Minden Gross LLP in Toronto. He can be contacted at (416) 369-4136 or [email protected].