Zero-tolerance policies don't usually hold up, even in safety-sensitive workplaces, says lawyer

Zero-tolerance policies usually don’t hold up to legal scrutiny, particularly when human rights are involved.

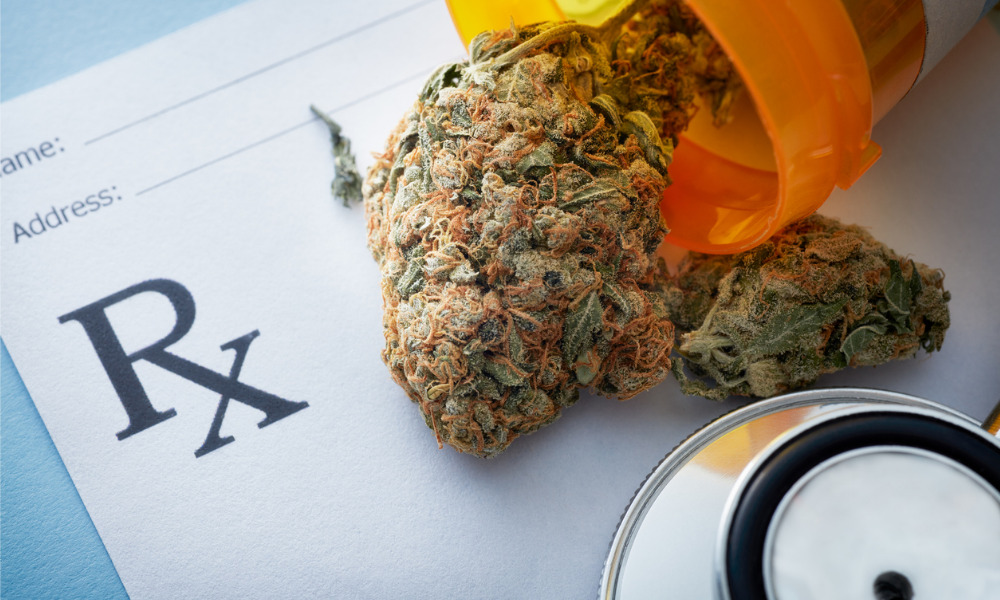

An Ontario arbitrator reinforced that concept when it ruled that an employer’s total prohibition of medical cannabis for a safety-sensitive position was discriminatory — a decision that’s not surprising to Sharaf Sultan, an employment lawyer and principal of Sultan Lawyers in Toronto.

“Many employers may think that if they say they have a zero-tolerance policy that it’s black and white, but in context of human rights, that isn't usually the case.”

A workplace drug and alcohol testing is a no-go without evidence of a real problem at the workplace, according to a B.C. arbitrator.

Aircraft engineer

The worker was an aircraft maintenance engineer (AME) for Ornge Air in Timmins, Ont., a not-for-profit provider of air ambulance and critical-care land ambulance services. As an operator of fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters, Ornge is subject to federal legislation and regulations.

The worker’s job duties included maintaining aircraft to high safety standards in a noisy, safety-sensitive environment. The Timmins base only had two AMEs, so they alternated weeks being on call during evenings and weekends. While on call, the worker had to be available by phone at all times.

In January 2018, the worker was diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. His doctor eventually prescribed medical cannabis in April 2020.

The worker advised his supervisor of his prescription in accordance with the Ornge drug and alcohol policy, which banned the use of cannabis at any time, regardless of whether it was recreational or prescribed, in accordance with Transport Canada’s safety rules. The policy didn’t prohibit the use of prescription medication.

The differentiation between medical cannabis and other prescription medication is one area that should have raised a warning flag for potential accommodation trouble, says Sultan.

“The cultural views regarding cannabis are evolving quickly and employers need to make sure that they’re caught up with that,” he says. “Plus, it's also being respected as a medical treatment, so I think that it's important for employers to keep in mind that they need to look at cannabis in a different way than they may have in the past.”

The worker’s doctor indicated that the level of prescription meant that it would remain in the worker’s system for seven to eight hours after being consumed and the period of probable impairment would be five to six hours. If the worker used the prescription as discussed — not using it up to 10 hours before the beginning of his workday — there shouldn’t be any negative effects on his work performance or safety, the doctor added.

A Newfoundland and Labrador employer discriminated against a worker taking medical marijuana when it identified him as a potential workplace risk.

Temporary accommodation

The worker was temporarily assigned to a non-safety-sensitive position. His prescription was originally for a 10-week period, but it was extended and the worker continued in the accommodated position until Feb. 4, 2021.

The worker underwent an independent medical exam (IME) and the examining doctor concluded that the worker “would not be fit for duties for his safety-sensitive job.” Ornge determined that the worker was in violation of the zero-tolerance drug and alcohol policy and sent him home. The company took the position that on-call duty was part of the AME job and the worker couldn’t meet the requirements if he was consuming cannabis outside of the normal shift hours.

“The expert was of the mindset that there could be an issue with THC levels, impairing the individual such that they couldn't safely do their role,” says Sultan. “But it seems that that's where the analysis ended, whereas it really should have been, in the spirit of all human rights legislation across the country, to work within a co-operative manner with the employee. That means to participate in a joint venture, if you want to call it that, towards finding a solution.”

The worker was on paid sick leave for two weeks and then received short-term disability benefits, which paid him 75 per cent of his salary.

The union filed grievances claiming that Ornge discriminated against the worker on the basis of disability by refusing to schedule him for work, and that the drug and alcohol policy was discriminatory relating to the use of medically prescribed cannabis.

Reasonable steps?

The arbitrator found that Ornge took reasonable steps in the first phase of accommodation by collecting information, arranging an IME, and accommodating the worker in a temporary position. However, the policy didn’t provide any guidance on how to treat an employee in a safety-sensitive position with an ongoing prescription for medical cannabis.

This was problematic, according to Sultan.

“They basically had zero tolerance for cannabis, for both on- and off-duty, for any safety-sensitive position. And I understand, to a certain extent, their rationale, because they were of the mindset that this is a safety-sensitive role. They also felt that it was in compliance with Transport Canada’s standards for safety. But the issue is, it still doesn't follow human rights legislation.”

The arbitrator noted that the IME doctor said that the worker wouldn’t be fit for his safety-sensitive job on his prescription, but she didn’t indicate that a zero-tolerance standard was required for a safety-sensitive position, rather than adjustment to the prescription or some other form of accommodation.

The arbitrator determined that Ornge’s drug and alcohol policy wasn’t reasonable in that it treated prescribed medical cannabis differently from other prescription drugs. This was discriminatory treatment for employees with medical disabilities requiring treatment with medical cannabis, and it breached the collective agreement and the Canadian Human Rights Act, said the arbitrator.

The decision is a cautionary tale against inflexible zero-tolerance policies, according to Sultan.

“I think you're in a much better position as an employer to leave the window open slightly, unless it's clear that it is impossible to accommodate. It's possible that there are scenarios in which that could be the case, but it's hard to imagine many of them. I think you're in a better position as an employer to just draft policies that have flexibility built in, and then you absolutely can say no if you investigate it [and accommodation isn’t possible].”

See Ornge Air and OPEIU (DeGeit), Re, 2021 CarswellNat 5623.