Toronto hospital recognized for leadership in workplace mental health

(Note: This article originally appeared in Canadian HR Reporter Weekly, our new digital edition for subscribers. Sign up today to make sure you don't miss future issues: www.hrreporter.com/subscribe.)

Back in 2013, the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace was launched by the Mental Health Commission of Canada. Since then, many organizations have sought to adopt the set of guidelines, tools and resources meant to promote mental health and prevent psychological harm.

Michael Garron Hospital (MGH) in Toronto is one such employer, and it has successfully implemented 95 per cent of the recommendations as it vies to improve the health of its employees, physicians and volunteers.

The hospital’s efforts were recently rewarded — in June, it became the first hospital in the country to earn a Canada Order of Excellence from Excellence Canada for its national leadership in workplace mental health. Through its Mental Health at Work Program, Excellence Canada certifies employers in meeting the requirements of the standard.

Years of hard work

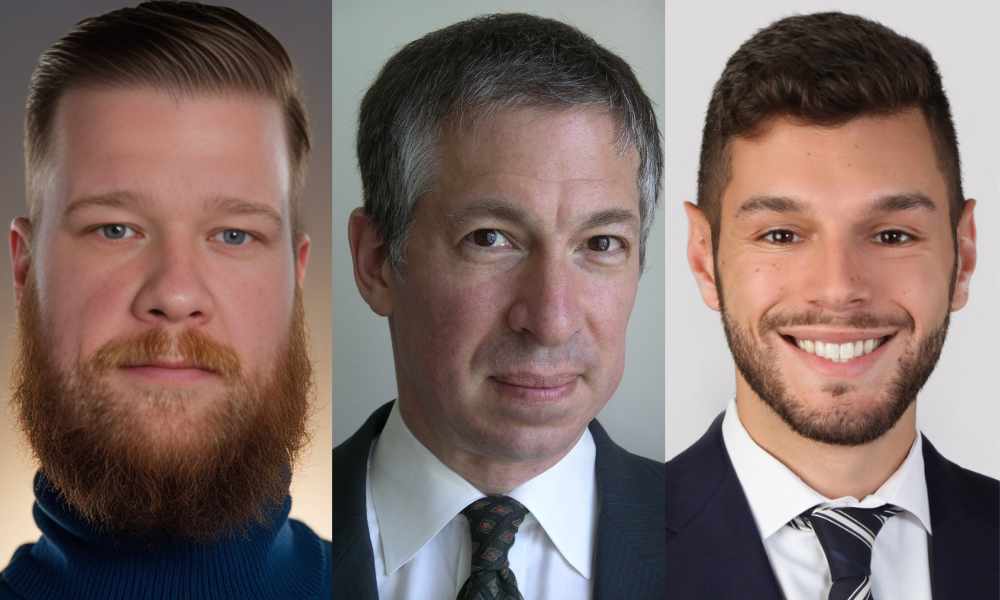

The standard serves as a road map to better guide and develop the hospital’s strategic plan around what needs to be accomplished and what needs to be targeted, according to Phillip Kotanidis, CHRO at Michael Garron Hospital (formerly East York General Hospital).

“It was important for us to publicly declare we’re committed to mental health, both to our staff and our community. It provides the recognition that should be provided for something this important.”

Health-care workers face more of a strenuous work environment than the average worker, he said.

“They’re constantly bombarded with traumatic events that are occurring, especially in our emergency department, so the level of resilience needs to be much higher… For us to be able to take care of our patients who are becoming more complex, more demanding, our front-line or patient-facing staff have to be well cared for, so their mental health, their physical well-being has to be a priority in order to provide excellent patient care.”

MGH started to work on the cultural shift several years ago, and paired up with Excellence Canada to pursue its goals, according to Christine Devine, wellness co-ordinator at MGH.

“The beauty of working with Excellence Canada is not only do they give you a guide to implement it incrementally but you go through a verification process where people outside of your sector come in and evaluate you and they give you really good ideas for opportunities to developing strengths, and look at different things you might not consider because you have your lens. So, for us, it’s been a really valuable experience to pursue it.”

MGH has introduced several initiatives around mental health in recent years, including Leading a Mentally Healthy Workplace Certification — a Queen’s University-accredited program focusing on mental health stigma, signs and symptoms, coaching and support, accommodation and return to work. To date, 80 hospital leaders have completed the program.

Since 2014, more than 912 new hires have attended emotional intelligence training through the hospital, while more than 400 have completed LGBTQ inclusivity training.

MGH has also facilitated more than 22 workshops on a respectful workplace and harassment and bullying prevention.

“We wanted to target those passive-aggressive behaviours that maybe won’t make it to an incident report, won’t make it to a full-blown official complaint, but they’re causing people to go off sick, they’re having people not be engaged in their work and not want to be here because of it,” said Kotanidis.

The program shows how these behaviours are not acceptable, and can erode engagement and well-being at work, he said, “so gossiping, exclusion, more minor things on the spectrum of harassment and bullying, but still harassment and bullying. And we’ve seen a lot of uptick on that and appreciation around those (workshops).”

All patient-facing staff also participate in mandatory, in-person workplace violence prevention workshops in addition to mandatory, annual online training for all employees.

“We believe you can’t have psychological health and safety if you don’t have physical safety, so we provide onsite de-escalation tactics — everybody needs to go through the training yearly — and we work jointly with ONA (Ontario Nurses Association), our union partner, to ensure our nurses and other front-line staff are well-versed in the workplace violence prevention and de-escalation tactics,” said Kotanidis.

Other initiatives at the hospital include: a daily risk matrix, self-care lunch-and-learn sessions, compassion fatigue education, an annual wellness fair and Indigenous cultural safety training.

Tracking success

MGH also uses a psychological health and safety scorecard to track the effectiveness of planning and programming correlated to the 13 psychosocial factors outlined in the standard, and the basic psychological and self-fulfillment needs defined in Maslow’s Hierarchy.

The hospital has seen encouraging ROI numbers in recent years, such as a decrease in overall health-care costs and prescription costs related to mental health, along with reductions in short- and long-term disability claims for mental health absences. However, MGH has also gone through major changes recently, with a new CEO and major construction projects, so the metrics have varied.

“The positive is people are talking about it now. They’re coming forward and saying, ‘I’m having difficulty with this,’” said Devine.

Physicians, for example, have developed a task force for physician burnout.

“We took that as a really positive sign that we have created a safe space for people to say, ‘We need resources, we need help,’ and then you have a starting point,” she said.

It’s also hard to gauge the numbers, internally and externally, according to Devine.

“How do you correlate that what you’re doing particular to mental health is the cause for a positive or a negative? And, really, is it about that? Or is it about the moral obligation?” she said.

“Our senior leadership team from the get-go put this as priority in the corporate strategic plan… because they felt it was the right thing to do, not because they expected to see any changes in numbers whatsoever — which I think is pretty exceptional and speaks to the kind of culture we have.”

SIDEBAR

Health-care challenges

Health-care workers face unique stresses, according to Sean Healey, a social worker at Michael Garron Hospital (MGH) in Toronto.

“Nurses have patients who pass away, and in mental health, you have patients who either are coming in with attempted suicides and have in some cases successfully committed suicide; you may have co-workers who get assaulted by patients or there’s a violent incident… and it’s traumatic when it happens,” he said. “You really never know what’s around the corner, what you’re going to be faced with.”

The “trauma-infused” environment can weigh on health-care professionals, said Christine Devine, wellness co-ordinator at MGH.

“Many people feel if they come forward, they will be seen as unable to do their job, they will lack credibility, they might be putting themselves in jeopardy of some sort of malpractice suit because how can you possibly do your job if you’re unwell? And there’s a lot of God complex and perfectionism in health care: ‘We should have known what we were getting ourselves into, we should be able to handle it, suck it up’ — that kind of mentality.”

It’s important to communicate to people that this is a normal consequence of them doing their job really well, she said, “and that it’s our job as employees and employers to create a space where it’s OK to say, ‘That had an affect on me and I need to talk about it’ or ‘I need help’ or ‘I need you to coach me through this.’”